Author: Melisa Téves

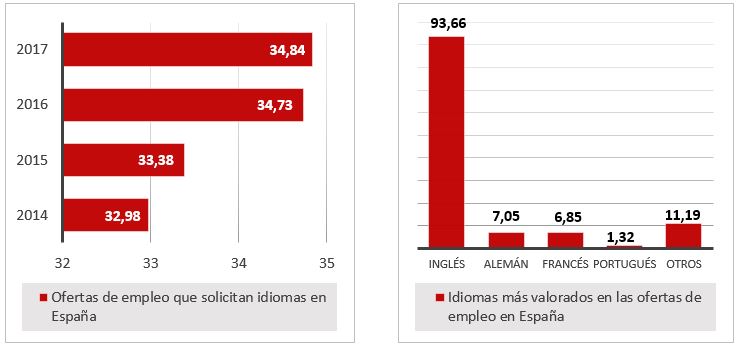

In today’s job market, having a good level of English has turned from being a desirable tool that provides added value to a candidate’s resume, to becoming indispensable when finding a job or accessing a better paid position. According to a recent report by Infoempleo and Adecco —published last October— 34.84% of job offers demand knowledge of at least one foreign language. Furthermore, this report reveals that English is an essential requirement in 93.66% of those offers; a fact that consolidates English as the language of business par excellence.

Source: Infoempleo Adecco 2017[1]

In order to respond to the growing demand for languages driven by the internationalisation of the business sector, some Spanish universities have begun to request their students to accredit an intermediate or upper-intermediate level of English (B1 – B2)[2] in order to obtain a bachelor’s degree, as well as to apply for an Erasmus scholarship. However, at Antonio de Nebrija University, we believe that these measures are not enough neither to guarantee the quality of education nor to improve the job prospects of our students. That is why we dare to go one step further by firmly committing to a language learning policy that allows our students to certify an advanced level of linguistic competence in English (C1) upon leaving university.

Taking into account the new challenges of language training in Nebrija, the Institute of Modern Languages (ILM, by its initials in Spanish), under the direction of the Vice-rectorate of Transversal Integration, has designed the Diploma in English Professional Communication (DEPC); a compulsory programme for all the students of in-campus degrees of the university. Its main objective is to provide the students with the necessary intercultural and professional language skills to develop in a globalized working environment. This new teaching-learning model, which will replace the current Diploma in English Professional Skills, is the result of years of research into the different approaches and methods applied to language learning, and of a profound process of reflection on the needs and challenges faced by our students. It is in that context that the DEPC was born to make up for the learning deficiencies that emerged after nine years of implementation of the current diploma. Furthermore, it aims to break with the inertia of the traditional learning process that often leads to lack of motivation, frustration and absenteeism in the classroom.

For the reasons mentioned above, the DEPC has incorporated the project-based learning model, opting for a multidisciplinary approach that stimulates collaborative work and allows the development of diverse transversal competences such as autonomous learning, responsibility, self-criticism, and the ability to interact with others and solve problems. Our methodological model bets on learning in a practical and interactive way the diverse grammatical, lexical and cultural aspects of the language. Moreover, it puts special emphasis on the development of communicative competences, since these are the most demanded in the labour market.

As Bernadette Holmes, campaign manager of the Speak to the Future program, explains in her essay «The Age of the Monolingual Has Passed: Multilingualism Is the New Normal»:

A great deal of professional activity in all sectors of employment relies on leveraging relationships. When clients come from a different language community, if a company can connect using a common language, this adds to their credibility and to their competitive advantage. Contracts can be won or lost on an organisation’s ability to communicate. (2016: 184)[3]

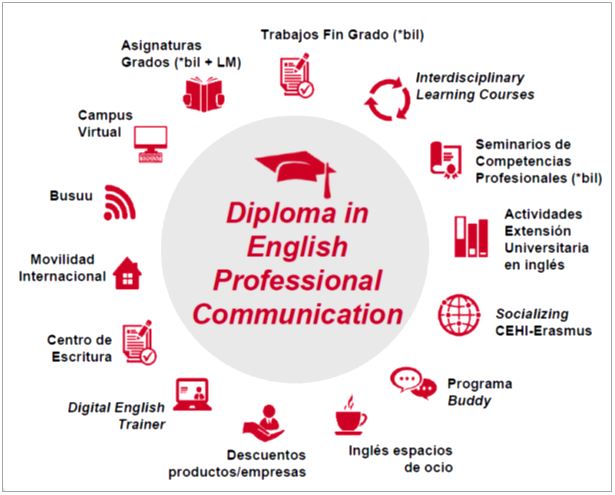

However, it is clear that a project as ambitious as this one needs an entire ecosystem of support which maximizes the hours of contact with the language. For this purpose, the Vice-rectorate of Transversal Integration has launched relevant actions that seek to promote the use of the language outside the English classrooms, and make students the main protagonists of their learning and personal growth. Said actions or touchpoints will be key pieces in the linguistic training of our students, not only to complete the teaching hours of the DEPC, but also to integrate the use of English in our educational community. For instance, the international mobility programmes, the bilingual subjects offered in the degree, the Buddy programme or the Socializing CEHI-Erasmus, just to mention some of them.

English promoting Touchpoints Nebrija. Source: Nebrija

As professionals in the field of teaching English as a second language, we take up this challenge with commitment and enthusiasm, since we believe that the current situation requires competent professionals who are able to make a flexible use of English for social, academic or professional purposes. We also understand that the globalisation of the labour market must bring with it a change of mentality. This change leads us to understand that English plays a hegemonic role as an international lingua franca, and that any professional, no matter how well prepared, will be excluded from any recruitment processes unless a high command of the language is proved. That is why we defend the urgent need to leave behind the stigmata reflected in well-known phrases such as «I understand English, but I don’t speak it» or «I’ve always been bad at English». It is time to begin a new tradition of linguistic excellence, one that brings us closer to countries with solid language learning policies such as Sweden, Norway or Denmark. Only then will we be able to be part of a globalized world without communication barriers that hinder our progress.

Melisa Téves

Instituto de Lenguas Modernas

Centro de Estudios Hispánicos

[1] https://iestatic.net/infoempleo/documentacion/Informe-Infoempleo-Adecco-2017.pdf

[2] All levels mentioned are based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR).

[3] See: Holmes, Bernadette. “The Age of the Monolingual Has Passed: Multilingualism Is the New Normal.” Employability for Languages: A Handbook, edited by Erika Corradini et al., Research-Publishing.net, 2016, pp. 181–187