Autora: Melisa Téves

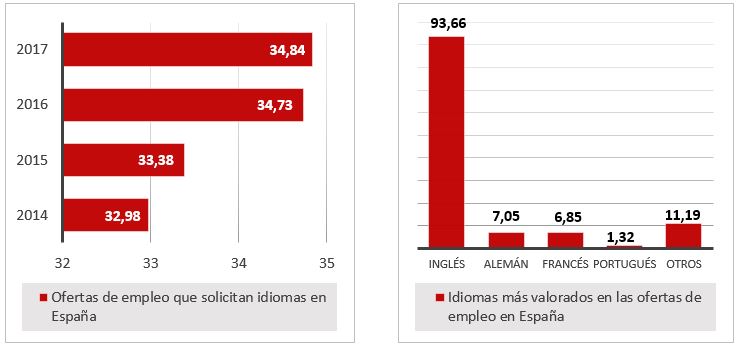

En el mercado laboral actual, contar con un buen nivel de inglés ha pasado de ser una herramienta deseable que proporciona un valor añadido al curriculum vitae de un candidato, a convertirse en un requisito indispensable a la hora de encontrar trabajo o acceder a un puesto mejor remunerado. Según un reciente informe elaborado por Infoempleo y Adecco, publicado el pasado mes de octubre, el 34,84% de las ofertas de trabajo requiere conocer al menos un idioma extranjero. Asimismo, este informe nos revela que el inglés es un requisito imprescindible en el 93,66% de dichas ofertas; lo que lo lleva a consolidarse como el idioma de los negocios por antonomasia.

Imagen: Informe sobre el requerimiento de idiomas. Fuente: Infoempleo Adecco 2017[1]

A fin de responder a la creciente demanda de idiomas impulsada por la internacionalización del sector empresarial, algunas universidades españolas han empezado a exigir a sus alumnos que acrediten un nivel intermedio o intermedio alto de inglés (B1 – B2[2]) para poder obtener el título de grado, así como para optar a una beca Erasmus. No obstante, en la universidad Antonio de Nebrija creemos que dichas medidas no son suficientes para garantizar la calidad educativa y mejorar las perspectivas laborales de nuestros alumnos. Es por ello que nos atrevemos a ir un paso más allá apostando firmemente por un aprendizaje de idiomas que permita a nuestros estudiantes certificar un nivel avanzado (C1) de competencia lingüística en inglés al egresar de la universidad.Fuente: Infoempleo Adecco 2017[1]

Teniendo en cuenta los nuevos retos de formación lingüística de la Nebrija, el Instituto de Lenguas Modernas (ILM), bajo la dirección del Vicerrectorado de Integración Transversal, ha diseñado el Diploma in English Professional Communication (DEPC); un título propio obligatorio para todos los estudiantes de grados presenciales de la universidad, el cual tiene como objetivo principal dotar al alumnado de las competencias lingüísticas interculturales y profesionales necesarias para desenvolverse en un entorno laboral globalizado. Este nuevo modelo de enseñanza-aprendizaje, que sustituirá al actual Diploma in English Professional Skills, es el resultado de años de investigación de los diferentes enfoques y métodos aplicados a la enseñanza de inglés, y de un profundo proceso de reflexión sobre las necesidades y desafíos a los que se enfrentan nuestros estudiantes. Es así como el DEPC nace para suplir las carencias de aprendizaje que afloraron tras nueve años de implantación del actual diploma, y pretende romper con la inercia del proceso de aprendizaje tradicional que suele desembocar en falta de motivación, frustración y absentismo en las aulas.

Por esta razón, el DEPC ha incorporado el modelo de Aprendizaje Basado en Proyectos, decantándose por un enfoque multidisciplinar que estimule el trabajo colaborativo y permita desarrollar diversas competencias transversales como la autonomía del aprendizaje, la responsabilidad, la capacidad de autocrítica, y la habilidad de interactuar con otros y resolver problemas. Nuestro modelo metodológico apuesta por aprender de forma práctica e interactiva los diversos aspectos gramaticales, léxicos y culturales del idioma, poniendo especial énfasis en el desarrollo de las competencias comunicativas, ya que son éstas las de mayor demanda en el mercado laboral. Tal y como explica Bernadette Holmes, jefa de campaña del programa Speak to the Future, en su ensayo “The Age of the Monolingual Has Passed: Multilingualism Is the New Normal” [La era de los monolingües ha terminado: El multilingüismo es la nueva normalidad]:

“Una gran parte de la actividad profesional en todos los sectores del empleo se basa en el fortalecimiento de las relaciones. Cuando los clientes provienen de una comunidad lingüística diferente, si una empresa puede conectarse utilizando un idioma común, esto aumenta su credibilidad y su ventaja competitiva. Los contratos pueden ganarse o perderse por la capacidad de una organización para comunicarse.” (2016: 184)[3]

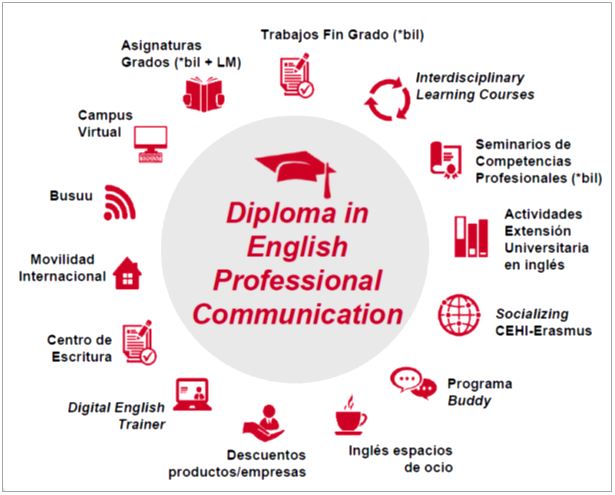

No obstante, es evidente que un proyecto tan ambicioso como éste ha de necesitar todo un ecosistema de apoyo que maximice las horas de contacto con el idioma. Por esta razón, el Vicerrectorado de Integración Transversal ha puesto en marcha numerosas acciones que buscan impulsar el uso de la lengua fuera de las aulas de inglés, y convertir a los alumnos en los principales protagonistas de su formación y crecimiento personal. Estas acciones o puntos de contacto con el idioma (touchpoints) serán piezas clave en la formación lingüística de nuestros estudiantes, no solo para completar las horas lectivas del DEPC, sino para integrar el uso del inglés en nuestra comunidad educativa, tal y como lo llevan haciendo los programas de movilidad internacional, las asignaturas bilingües ofertadas en los grados, el programa Buddy o el Socializing CEHI-Erasmus.

Imagen: Touchpoints Nebrija: Puntos de Contacto con el idioma inglés. Fuente: Nebrija.

Como profesionales en el ámbito de la enseñanza de inglés como segunda lengua, asumimos el reto del C1 con compromiso e ilusión, sabiendo que la coyuntura actual requiere profesionales competentes que sean capaces de hacer un uso flexible del inglés para fines sociales, académicos o profesionales. Asimismo, entendemos que la globalización del mercado laboral debe traer consigo un cambio de mentalidad que nos lleve a comprender que el inglés juega un papel hegemónico como lengua franca internacional, y que cualquier profesional —por muy preparado que esté— quedará fuera de los procesos de selección si no es capaz de demostrar un alto dominio del idioma. Por todo ello, defendemos la imperiosa necesidad de dejar atrás los estigmas reflejados en frases tan conocidas como “yo lo entiendo, pero no lo hablo” o “a mí el inglés siempre se me ha dado mal”, y comenzar una nueva tradición de excelencia lingüística que nos acerque a países con sólidas políticas de aprendizaje de idiomas como Suecia, Noruega o Dinamarca. Sólo así podremos ser parte de un mundo globalizado sin barreras de comunicación que obstaculicen nuestro progreso.

Melisa Téves

Instituto de Lenguas Modernas

Centro de Estudios Hispánicos

[1] https://iestatic.net/infoempleo/documentacion/Informe-Infoempleo-Adecco-2017.pdf

[2] Todos los niveles a los que se hace mención se basan en el Marco Común Europeo de Referencia para las Lenguas (MCERL)

[3] Ver: Holmes, Bernadette. “The Age of the Monolingual Has Passed: Multilingualism Is the New Normal.” Employability for Languages: A Handbook, edited by Erika Corradini et al., Research-Publishing.net, 2016, pp. 181–187